People often associate air quality with comfort, outdoor pollution, or visible factors such as smoke and or dust. However, research from Harvard's Healthy Buildings Program and the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that indoor environments can contain pollutant levels up to five times higher than those found outdoors, as airborne contaminants tend to build up in enclosed spaces. Given that most people spend between 80% and 90% of their time indoors, indoor air quality has significant implications for health and well-being. Studies published in the Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology and other health research journals have linked prolonged exposure to poor indoor air quality with a wide range of adverse effects, including an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, cardiovascular dysfunction, immune impairment, and mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Degraded air quality can also compromise cognitive performance, reduce concentration, and limit problem-solving ability. To understand and address these widespread effects, it is crucial to examine the key components of indoor air quality.

CO₂ has historically been used as the primary metric for measuring indoor air quality, as elevated levels suggest inadequate ventilation and poor air circulation. The commonly cited threshold of 1000 parts per million (ppm) was established in the 19th century, based largely on odor perception rather than scientific evidence related to health or cognition. As a result, this standard is outdated, does not reflect modern research, and is unsuitable to a contemporary context.

Today, CO₂ is tracked not due to its odor but rather because elevated concentrations act as environmental stressors that influence both physiological and cognitive performance.

The 2025 ASHRAE Indoor Carbon Dioxide, Ventilation, and Indoor Air Quality Brief, along with studies from Harvard’s Healthy Buildings Program, shows that cognitive decline begins to occur at concentrations above 800 ppm, with individuals reporting sluggishness and difficulty concentrating. When CO₂ levels reach between 1,000 and 1,500 ppm, performance on complex tasks that require executive functioning and problem-solving declines significantly. In fact, for every 500 ppm increase in CO₂, response times are increased by 1.4-1.8%.

Beyond cognitive effects, the ASHRAE brief and research from Harvard highlight that the poor ventilation indicated by high levels of CO₂ increases the likelihood of airborne disease transmission. Studies published in Clinical Infectious Diseases further confirm that in poorly ventilated spaces, airborne diseases and viruses, like influenza or COVID-19, can linger in stagnant indoor air. This means that even brief contact with individuals who may be unknowingly unwell can pose a significantly higher risk of infection in spaces with poor ventilation.

While CO₂ remains an important indicator for indoor air quality, it alone cannot capture the full picture. CO₂ concentrations provide valuable insight into ventilation, capacity, and circulation. However, they do not reflect the cleanliness of the air or the presence of other harmful pollutants. To develop a more comprehensive understanding of indoor air quality, additional factors such as particulate matter and organic compounds must also be taken into account.

Another major contributor to poor indoor air quality is VOCs, which are carbon-based chemicals that quickly evaporate at room temperature. VOCs can be biogenic, originating from natural sources and reacting quickly with oxidants in the air, or anthropogenic, coming from human activities and materials like cleaning products, electronic equipment, adhesives, and more. According to research published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and PublicHealth, mundane items like disinfectants, office furnishings, and monitors can release VOCs into the indoor environment.

As explained by researchers at the Fraunhofer WKI Institute, writing in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, VOCs are particularly dangerous because they act as precursors, reacting with other airborne substances to then form secondary pollutants that are often even more harmful than the original compounds. Long-term exposure to VOCs has been associated with respiratory irritation, neurological effects, chronic diseases, and even certain cancers such as leukemia. Reviews in Building and Environmental also note that people exposed to high levels of VOCs often experience symptoms stemming from “sick building syndrome,” including headaches, dryness, dizziness, and fatigue.

A recent study by the Harvard’s Healthy Buildings Program found that approximately 90% of conventional office buildings exceeded WHO’s recommended thresholds for total VOC levels. This underscores how common inadequate air quality is in workplaces. On the other hand, Harvard’s landmark COGfx Study also shows that offices with improved ventilation, low-emission materials, and higher levels of air filtration can have up to 10 times lower VOC levels. Workers in these environments consistently score higher on cognitive function tests. Therefore, while VOCs are both harmful and widespread, their concentrations and effects can be significantly reduced through improved ventilation and selecting materials that limit emissions in the indoor environment.

Another major component of indoor air quality is fine particulate matter, more specifically, PM2.5. These microscopic particles or droplets, less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, are able to bypass the body’s natural defenses due to their small size, allowing them to penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. Research published in Urban Climate and Building and Environment shows that, on average, indoor environments contain approximately 26.7 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic meter, and about 87% of all airborne particles indoors are classified as PM2.5.

Studies from Harvard’s Healthy Buildings Program have shown that exposure to high levels of PM2.5 has been linked to significant declines in cognitive performance, with every 10 micrograms per cubic meter increase being associated with a 0.8-0.9% slower response time. In addition to cognitive effects, these particles can act as vehicles for airborne pathogens, increasing the risk of airborne disease transmission, a concern underscored by both ASHRAE and WHO.

On the other hand, when air purifiers were introduced to indoor settings in one office-based intervention study, average PM2.5 levels dropped significantly to approximately 3.7 micrograms per cubic meter. Participants in these cleaner-air environments reported higher satisfaction with air quality, greater thermal comfort despite unaltered temperatures, and increased overall productivity. Therefore, significant reductions in PM2.5 enhance perceived air quality, increase efficiency, and protect broader health and well-being.

It is now clear that indoor air quality has a profound influence on health, well-being, and productivity. Indoor air quality is also shaped by several interacting factors, including CO₂, VOCs, and PM2.5. Research shows that each of these components has been proven to negatively affect physical health, cognitive performance, and overall comfort and satisfaction when present in high concentrations. However, research also demonstrates that lower concentrations are both achievable and impactful, with significant improvements observed in focus, mood, and productivity when indoor air quality is optimized.

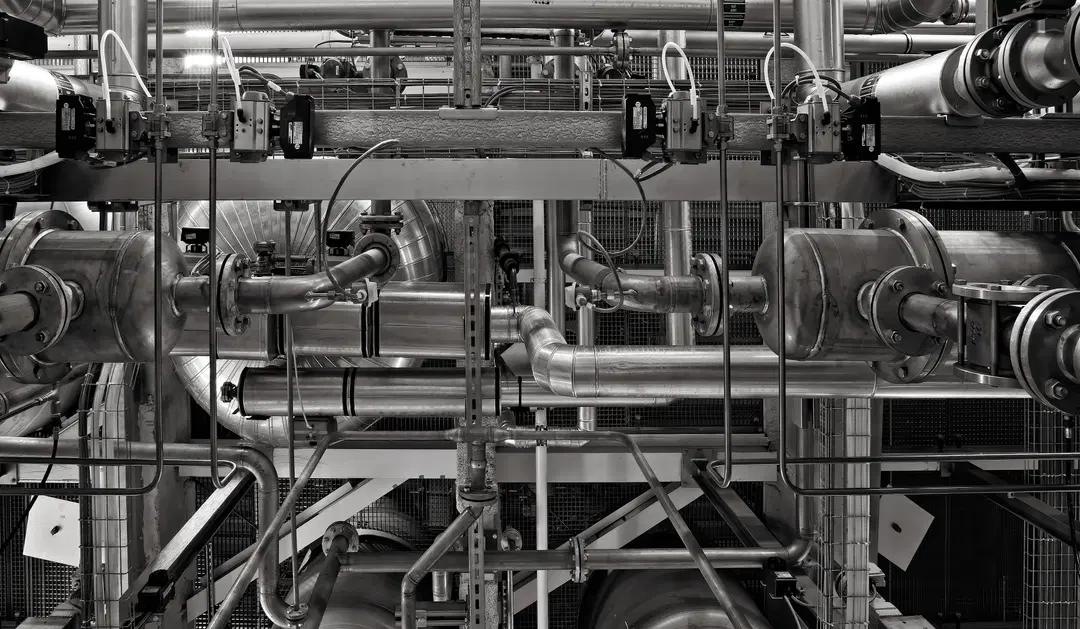

Addressing poor indoor air quality therefore requires a strategic and sustained approach. Ventilation, filtration, and building material selection all play critical roles, but their efficacy hinges on continuous monitoring and accurate measurement. Meaningful improvement depends on measuring air quality within its specific context, rather than adhering to out-of-date standards that fail to capture modern realities of the built environment. Furthermore, because air quality fluctuates with occupancy, activity, and environmental conditions, single-point measurements are insufficient to represent true levels and concentrations. Ongoing tracking, rather, allows for more robust insights, enabling interventions that foster more healthy, stable environments over time. With growing evidence, accessible monitoring technologies, and a clearer understanding of the factors involved, maintaining high indoor air quality is no longer aspirational but rather attainable and essential.